SSH and remote management

26 October 2021

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- What is SSH?

- Using SSH

- How does SSH work

- Configuring SSH

- Connecting to

linux.bathwith SSH - Connecting to machines through ssh sessions

- Using ssh to forward ports

- Exercises

- Credit

Introduction

SSH is an extremely widely used tool for connecting to computers remotely. In

this lab we are going to give a basic introduction to SSH, how it works, how to

use it, and then an example of how to use SSH to connect to linux.bath.

What is SSH?

SSH means Secure Shell. It is primarily used to access a command line environment on a remote machine. However SSH is more than that - it is a cryptographic network protocol for communicating securely. SSH can be used to secure any network service and while it is most commonly used for command line access, login, remote command execution, and file transfer it can be used for much more than that.

We will be primarily using SSH through command line programs in this lab. To find out more about command line environment look at our previous lab.

SSH is now supported by all the major desktop operating systems (Windows 10, macOS, the majority of Linux distros) and the vast majority of networking equipment uses SSH for remote management. Also most servers are controlled via SSH.

Using SSH

The most common SSH client is OpenSSH. It comes installed by default on

Windows 10, macOS, and most Linux distros, so it is the tool we will be

primarily using here.

If on Windows, we recommend you use one of two tools: either WSL2 or PuTTY.

The Windows Subsystem for Linux (WSL) runs a lightweight virtual machine with its own isolated Linux kernel. This lets you seamlessly use a Unix environment within Windows, giving you easy access for following along with these sessions. WSL1 used a translation layer to convert Linux kernel calls into Windows calls, so WSL2 is a big step up in terms of performance and experience.

WSL is really easy to setup - follow this link or google around on the subject to find an easy guide to installing it.

Once you have WSL2 running on your computer, you have full access to

OpenSSH through the command line as expected, and you’ll be able to

follow along with the rest of the session easily.

If you just want to use SSH, and don’t particularly care about the other benefits of the Unix kernel, there are alternative SSH clients. PuTTY is the most common of these, and supports SSH and SCP, along with many other transfer protocols. PuTTY is easily downloadable from here, and only takes seconds to install. It’s essentially a terminal emulator with a GUI over the top to make SSH and SCP setup easier.

To open a SSH remote command line connection in OpenSSH we use the command

ssh [address] where address is the address of the server you want to connect

to. Unless you have a configuration set for this address, OpenSSH will try to

login with your current username. If that’s not the behaviour you want you can

specify what username to use to login with by using the command

ssh [user]@[address] where user is your username. When you connect you

may be prompted for a password.

Alternatively you can execute a single command on a remote computer with the

command ssh ([user]@)[server] [command]. OpenSSH will show you the result of

the command.

alfierichards:~$ ssh ar2227@linux.bath.ac.uk

...

ar2227@linux.bath.ac.uk's password:

...

Last login: Mon Mar 1 10:04:55 2021 from 86.8.33.229

ar2227@linux2:~$

As always more details about ssh can be found on its man page or its tldr

page.

Transferring files over ssh

To transfer files with OpenSSH you need to use a different program - the SSH copy

program scp.

To send a file to a remote computer use the command

scp [file] ([user]@)[address]:[path], where file is the file you want to

send, and path is the directory where you want to save it on the remote

computer. This may look a bit confusing, but later we’ll show an example.

To copy a file from the remote computer use the command

scp ([user]@)[address]:[file] [path], where file is the file you want to copy

from the remote computer and path is where you want to store it locally.

For both directions of scp you can add the -r command and specify a

directory instead of a file - this will then recursively copy the directory and

all its contents.

alfierichards:~$ scp alfie.txt ar2227@linux.bath.ac.uk:~/alfiecopy.txt

...

ar2227@linux.bath.ac.uk's password:

alfie.txt 100% 298 37.1KB/s 00:00

How does SSH work

SSH is a protocol which many tools use. The protocol is structured into different layers, where each layer uses the previous layer to communicate.

The first layer is the Transport Layer. When you start an SSH connection this layer connects to the remote computer and sets up an encrypted secure connection between the two computers.

Next is the User Authentication Layer, which handles client authentication. This can either be with a password or with cryptographic private and public keys.

The last layer is the Connection Layer. This layer carries the channels of

information. You could have a shell channel, carrying input and output back and

forth, or it could be a file transfer channel, or many other types.

SSH also defaults to connecting over port 22. This can be changed if needed.

Configuring SSH

SSH allows you to configure some of its default behaviours. On Unix-like machines the configuration files are stored in ~/.ssh/config.

If you have servers you have to access often you can make custom configurations

for them by adding a Host [name] block. You can then add sections specifying the

username you want to use, and the hostname. Here you can also specify the

cryptographic key if you’re using it for authentication. The block for a server

will probably look something like this:

Host MyServer

Hostname 139.161.208.134

User myUser

You can also specify many more options that can be found in the ssh man page.

Connecting to linux.bath with SSH

linux.bath.ac.uk is an Ubuntu server setup for Bath students and staff. You

can login with your university username and password. In this example I’m going

to upload a Java file to linux.bath. I’ll then login to linux.bath, compile

the code and run it. I’ll save the output of the program and then copy it back

to my computer.

For this I will also assume a little bit of knowledge about some file management commands in Unix. To learn more about that look at our first lab.

The program is available here. It calculates the greatest common divisor of two numbers.

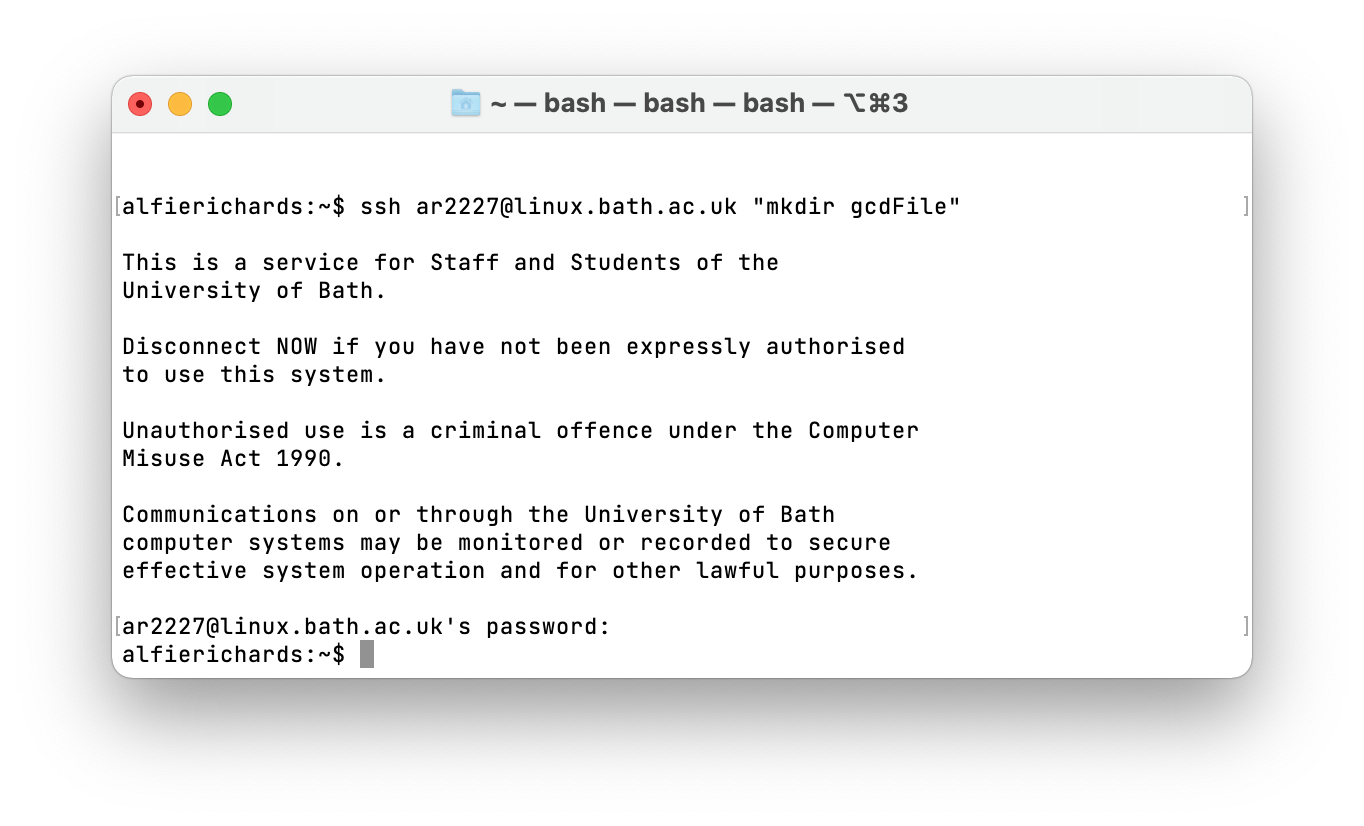

Firstly, I want to create a directory on the server. To do this I can do the remote

execution of a command -

ssh ar2227@linux.bath.ac.uk "mkdir gcdFile"

Note it’s now prompting me for my password.

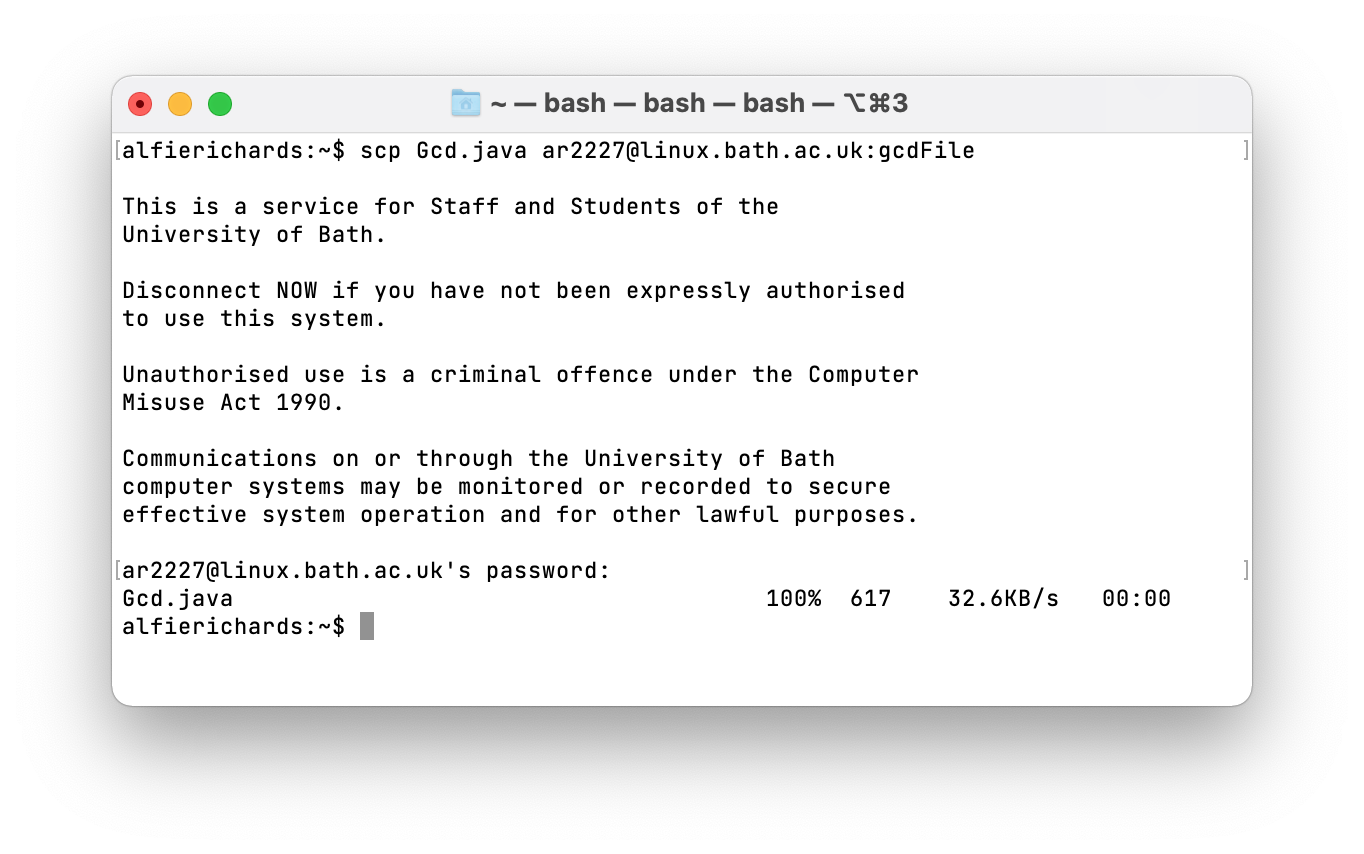

Next, I’m going to use scp to copy my code to the server. To do this I use the

command scp Gcd.java ar2227@linux.bath.ac.uk:gcdFile.

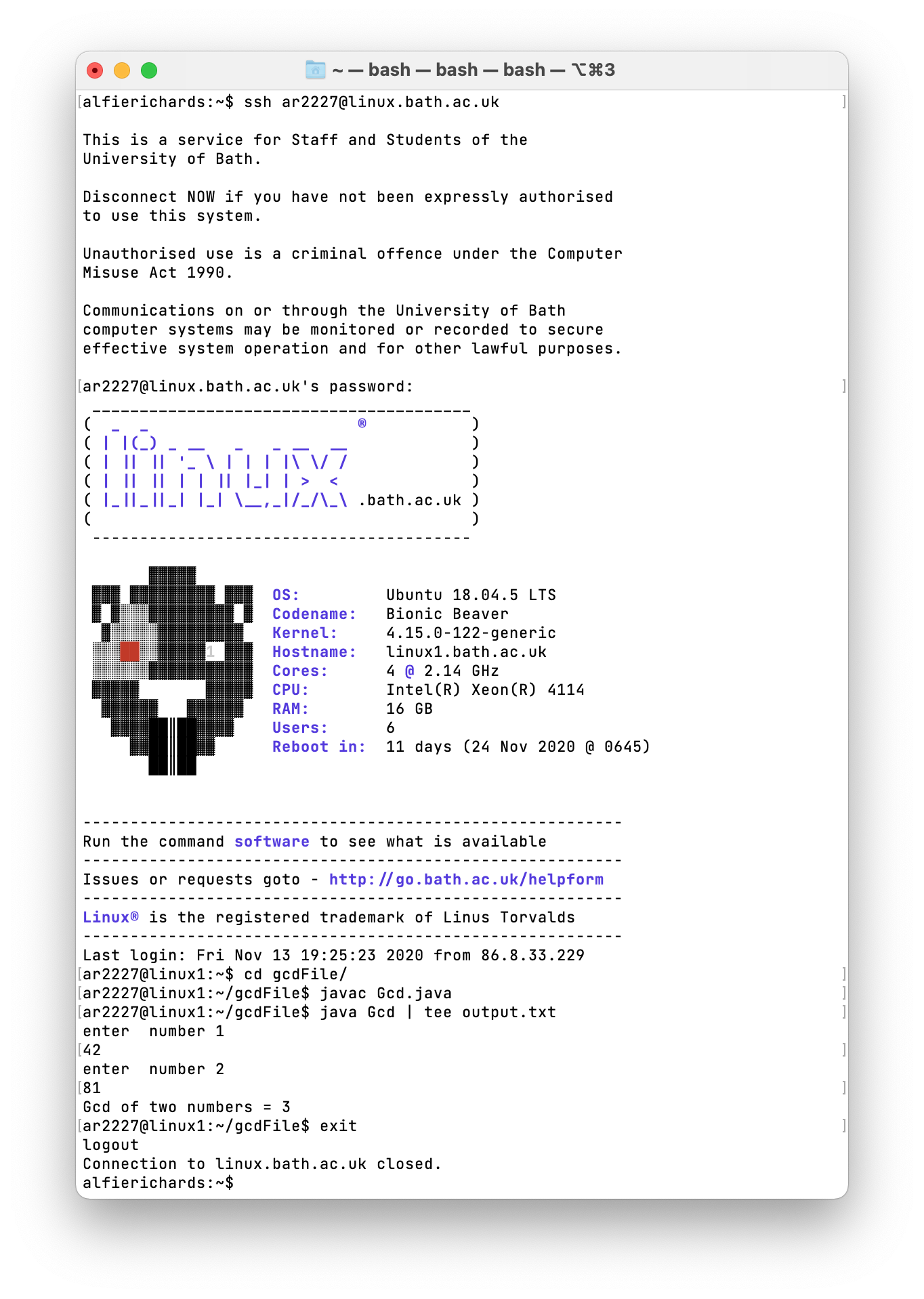

Then I need to open a remote shell on the server, compile my code, run it,

and save the output. To open the shell I’m going to run

ssh ar2227@linux.bath.ac.uk.

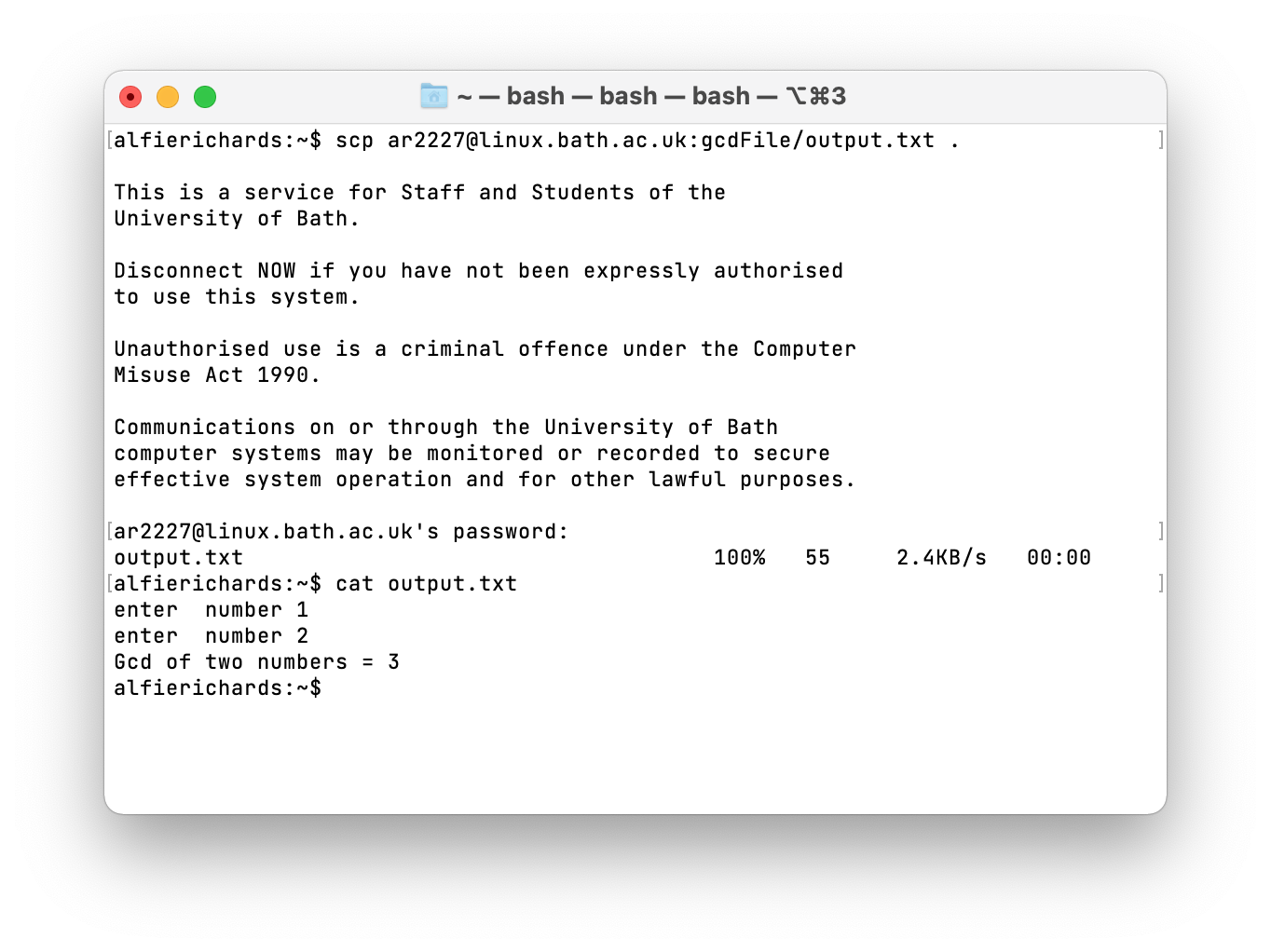

Then I’m going to copy the output file to my local computer with

scp ar2227@linux.bath.ac.uk:gcdFile/output.txt ..

And we’re done! We successfully used the remote server to compile and run our code.

Connecting to machines through ssh sessions

As an ssh session can be used to open a command line session on another machine, you can use that session to open another ssh session to another machine.

This is useful if you need to connect to a machine that is only accessible

within a local area network. For instance the machine used in Parallel Computing

CM30225 is only accessible from machines within the University of Bath network.

To access that machine externally we can first connect to the linux.bath

machines which are within the University network and then ssh from there to the

machine.

This is common enough for there to be a flag from which ssh will do it all for you.

alfierichards:~$ ssh -J ar2227@linux.bath.ac.uk cm30225.hpc.bath.ac.uk

Using ssh to forward ports

As mentioned earlier, ssh is a protocol which can be used to send anything.

For example, for AI research it is common to use Jupyter notebooks, which are usually accessed through a HTTP connection. Additionally you may want to use a remote compute cluster, but it would be a bad idea to make the jupyter notebook connection publicly accessible. We can use ssh to “tunnel” the HTTP connection to the remote machine.

To do this we will tunnel a port from the remote machine to a port on the local machine. Then when my local browser attempts to connect to the remote machine it will go through the tunnel and connect to the remote machine.

alfierichards:~$ ssh -L 9000:localhost:10000 ar2227@comp.cs.bath.ac.uk

ar2227@comp.cs.comp.ac.uk's password:

Welcome to Ubuntu 20.04.2 LTS (GNU/Linux 5.4.0-71-generic x86_64)

...

ar2227@comp:~$ jupyter notebook --port=10000

[I 15:28:58.758 NotebookApp] Serving notebooks...

Here I tunnel port 9000 from my local machine to the localhost 10000 port on a

remote machine on the Bath Computer Science compute cluster. Then I start a

Jupyter notebook session on the same port 10000. I can then connect to the

session by connecting to localhost:9000 on my local machine.

Remote development

Most IDEs now support remote development, where the IDE connects through SSH to a session running on a remote machine. Then all files and development happen on the remote machine, leaving your machine just running the GUI and SSH session.

This is very useful for certain projects where development becomes very expensive so portable machines wouldn’t be usable. Such as in many machine learning examples.

Exercises

- Connect to

linux.bathand have a look around, there will already be some files in there that come by default. - Copy some files to and from

linux.bath. You will be able to see them on the Bath files explorer website. - Look into using cryptographic keys for authentication. See if you can set one

up for GitHub or some other server. (

linux.bathdoes not support it). - Connect to

linux.bathand runmkhometo setup your Bath people page. You can get to your page atpeople.bath.ac.uk/[username]/

Credit

SSH research came from SSH.com which is a great website setup by the creator of SSH and from Wikipedia.

Written by Alfie Richards and Joe Cryer.

Additional help from:

- Dr Russell Bradford

- Søren Mortensen

Please sent any corrections here